Like a coroner conducting an autopsy, economist and Wayne State University Law School professor Peter J. Hammer recently performed a highly detailed dissection of the Flint water crisis, laying bare the various pathologies that led to the poisoning of Flint's water supply.

His diagnosis—contained in a 65-page report titled "The Flint Water Crisis, KWA and Strategic-Structural Racism"—was delivered as written testimony to the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, which last week held the second of three hearings on the disaster in Flint.

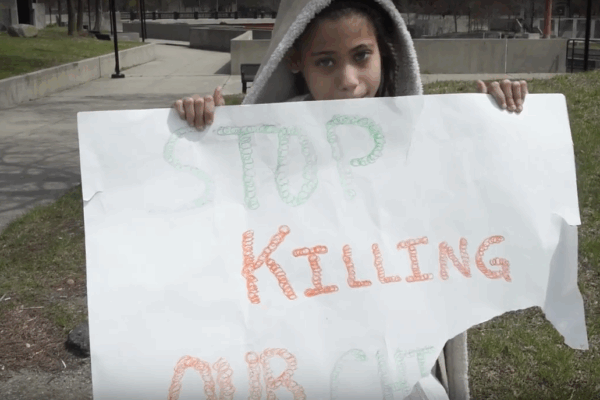

Hammer's report provides a devastating critique of the financially driven chicanery and political sleight of hand that resulted in lead contaminating the water supply of an impoverished, majority African-American city of nearly 100,000 residents.

And his report is a must-read for anyone hoping to understand the full scope of the systemic failures that led to this catastrophe, and the forces propelling them.

Consider, for instance, the report's overview of the crisis:

"Flint is a complicated story where race plays out on multiple dimensions. It is a difficult story to tell because many facts suggesting the State's real complicity in the tragedy are still being revealed. That said, three truths about Flint, race and water are beginning to resonate strongly.

"The first truth is how the entire Emergency Management regime and governor Snyder's approach to municipal distress and fiscal austerity serves as a morality play about the dangers of structural racism and how conservative notions of knowledge-&-power can drive decisions leading to the poisoning of an entire City.

" The second truth is the role strategic racism played in motivating actors at the Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA), Treasury, DEQ (Department of Environmental Quality) and various Emergency Managers to disregard the lives of the citizens of Flint in seeking initial approval of the KWA pipeline and how these same players manipulated rules governing bond financing in a way that cemented use of the Flint River as an interim drinking water source as a predicate for financing the distressed City's participation in KWA.

"The third truth is how the structural racism embedded in the first serves to enable and reinforce the strategic racism embedded in the second."

And then, there are some of the report's major findings:

- Building on information first disclosed by the Detroit Free Press, Hammer explains how, in order to finance Flint's $85-million share of the pipeline, the KWA, Michigan Department of Treasury, Department of Environmental Quality and the emergency managers worked together to find and exploit a tenuous loophole that allowed them to "manipulate bond finance rules" in a way that committed Flint to use the Flint River as an interim drinking water source while the pipeline was being built.

- The decision to approve the KWA pipeline was driven by politics, not economics, and was made without consideration of how the financially distressed city would both pay $85 million toward construction of the $285-million pipeline project and still come up with the estimated $25 million to $65 million needed to upgrade its Water Treatment Plant (WTP). The solution was to pay for the pipeline while foregoing the vast majority of necessary water plant improvements.

- In the end, the emergency manager spent only $8 million on upgrades before starting to use the Flint River as the full-time source of drinking water. These funds were "self-financed" out of money previously paid to the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD) for clean drinking water. Flint could not afford both to buy safe water from DWSD and finance needed KWA improvements to the WTP, prompting the decision to use the dangerously corrosive Flint River as the city's water supply while the pipeline was being built.

- Although it was officially an appointed emergency manager who made that call, Hammer points out: "Surprisingly, there is yet no clear answer to the questions of who made the decision to use the Flint River as the interim source of drinking water or when the decision was made."

- The Flint City Council agreed to join the KWA with the stipulation that it would commit to purchasing no more than 16 million gallons of water per day. Demonstrating the council's lack of any real authority, one of Flint's one of emergency managers unilaterally changed the deal, committing the city to buying 18 million gallons of water per day so that the KWA would have all the funds necessary to build a larger-diameter pipeline. In other words, a city on the brink of insolvency would be required to buy more water than it needed in order to ensure that the rest of Genesee would be able to get all of the water it needed.

- As the full extent of the crisis began to be revealed, the state attempted to shield itself from ownership of the disaster it had created by prematurely declaring Flint's financial crisis to be over—allowing for the withdrawal of emergency managers. "Treasury contrived the end of Flint's Emergency Management in April 2015 to avoid continued responsibility for the growing public health crisis," Hammer notes

- "The end of emergency management did not end Flint's legal obligation to continue using the Flint River," writes Hammer. "The Emergency Loan Agreement entered into with the State to finance Flint's continued $8-million deficit, prohibited Flint from unilaterally returning to DWSD for drinking water, ending its participation in KWA or reducing water rates without State approval." Flint was eventually able to return to the Detroit system after Gov. Rick Snyder issued an order allowing the city to switch back to the water supplied by the regional system.

"Nothing about what happened in Flint was accidental," concludes Hammer. "Flint needs to be understood as a morality play illustrating the dangers of Emergency Management and fiscal austerity. Flint needs to stand as a profound multi-generational testimony to the dangers of strategic-structural racism in the same manner as the Tuskegee (Syphilis Experiment) forever shames medical science."

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}

"The first truth is how the entire Emergency Management regime and governor Snyder's approach to municipal distress and fiscal austerity serves as a morality play about the dangers of structural racism and how conservative notions of knowledge-&-power can drive decisions leading to the poisoning of an entire City."