Britain's Guardian newspaper deserves kudos for two recent articles dealing with the issue of testing for lead in municipal water supplies. Although one is national in scope, both stories have direct links to Flint, and both build on reporting done last year by the ACLU of Michigan.

Of particular interest locally is a report that compares the location of Flint homes tested by the city and state for lead in late 2014 with historical data recently compiled by University of Michigan researchers, who identified where lead service lines are located throughout the city.

Here's what the Guardian found:

"Water testing from November and December 2014, seven months after Flint's disastrous switch to a new water supply, was heavily targeted at properties on the eastern and western fringes of the city. According to lead service line mapping conducted by the University of Michigan, these test sites mostly do not correspond with Flint 's network of 8,000 lead water pipes."

Just to make sure readers got the point, the Guardian reiterated that message:

"Flint's water testing from late 2014 misses the bulk of the city 's lead pipe network, instead focusing on areas which, in some cases, are a long way from any apparent source of lead."

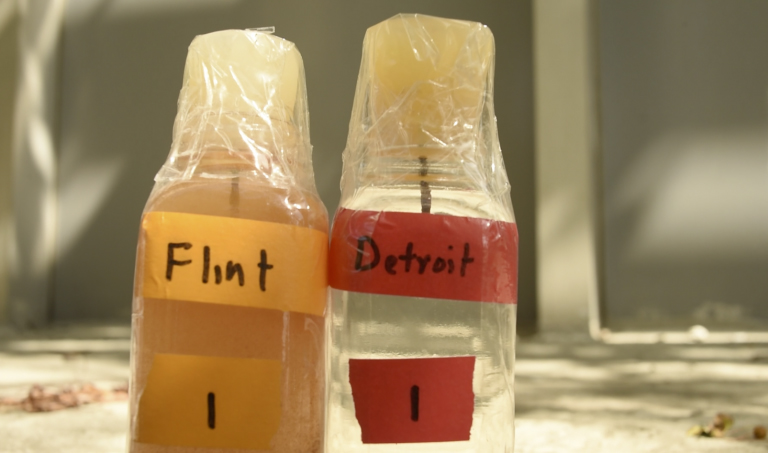

While under the control of a state-appointed emergency manager, Flint began using the highly corrosive Flint River as the city 's municipal water source. Because mandatory corrosion chemicals weren't used, lead from service lines and home plumbing began leaching into the water flowing to faucets – causing an untold number of the city's 100,000 residents to suffer from lead poisoning.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requires that only homes considered to be "high risk" in terms of lead exposure be tested. Homes with lead service lines – which connect the internal plumbing of individual homes to larger water mains – are a particular focus of that requirement.

Because the Flint tests primarily sampled homes in areas of the city without lead service lines, "just two out of the 100 tested homes had lead levels above the federal limit of 15 parts per billion (ppb)," the Guardian reported. "Thirty-seven had 'non-detectable' lead levels."

The Guardian's investigation further substantiates what the ACLU of Michigan documented last September when, in a videotaped interview with the ACLU, Flint water department official Mike Glasgow confessed that he could not substantiate the validity of reports filed with the state.

The ACLU of Michigan also disclosed that the city targeted homes along a stretch of Flushing Road where new infrastructure was installed in 2007.

As the Guardian reported, an "arrest warrant for Glasgow states that he admitted submitting information that falsely showed all of the water samples were taken from locations with lead service lines."

Glasgow, one of three people facing criminal charges for their alleged roles in the Flint water crisis, pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor count of willful neglect of duty in May as part of a deal with prosecutors. That deal reportedly involves the dismissal of a felony charge of tampering with evidence if Glasgow continues to cooperate with ongoing investigations.

A second Guardian article, published in the wake of the newspaper's investigation into the water crisis, reported, "At least 33 cities across 17 US states have used water testing 'cheats' that potentially conceal dangerous levels of lead…"

One of the primary "cheats" being used involves a water-sampling method known as "pre-flushing," which can reduce the amount of lead found in official samples.

The ACLU of Michigan helped bring the pre-flushing issue to light when it published an internal EPA memo last July that sounded the alarm about the practice being used in Flint.

The issue has now gone nationwide.

"They make lead in water low when collecting samples for EPA compliance, even as it poisons kids who drink the water," Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech scientist who helped expose the Flint crisis, told the Guardian. "Clearly, the cheating and lax enforcement are needlessly harming children all over the United States.

"If they cannot be trusted to protect little kids from lead in drinking water, what on Earth can they be trusted with? Who amongst us is safe?"

Edwards said in a press conference last week that, although lead levels are declining, people still need to use filters to protect themselves from lead. He warned that pregnant women and children under 6 still shouldn't use it all.

"Everyone knows the lead was high, and it is still too high, and we won't know for some months whether you are meeting the same standards as other cities in the United States," Edwards said.

Curt Guyette is an investigative reporter for the ACLU of Michigan. He can be reached at 313-578-6834 or cguyette@aclumich.org.

"If they cannot be trusted to protect little kids from lead in drinking water, what on Earth can they be trusted with? Who amongst us is safe?"