For centuries, black people have endured the brutal violence of racism and shouldered the burden of leading the fight against it. This fight includes fixing our criminal legal system, which is racist at its core, and anything but fair. The nation falls far short of a real “criminal justice” system.

Incarceration rates are proof of this. Though black people comprised just 14 percent of the state’s population in 2014, they made up 54 percent of the prison population. Our state lawmakers add, on average each year, about 40 new ways a person can be charged with a crime. This includes relying on lengthy sentences yet failing to address the complicated causes that are also rooted in racism, such as access to education, housing and job opportunities. As a result, Michigan suffers one of the longest averages for time served in the United States.

The data is chilling but the cost is all too human. Countless black families have loved ones locked behind bars. Black parents and their children that have been ripped apart. They are casualties of a destructive system. We can only end this issue with an unflinching attack on high incarceration rates as well as the racism that drives it. This is the aim of the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice.

During Black History Month, we celebrate those who have used the injustice in their own lives to fuel their resolve and empower others. The people, past and present, who have led the fight to end racism in all facets. From life in prison to community leadership. From jails to judges. From substance abuse to sentencing reform.

Michigan needs comprehensive criminal justice reform and it will only happen because of the leadership and work of the communities most impacted.

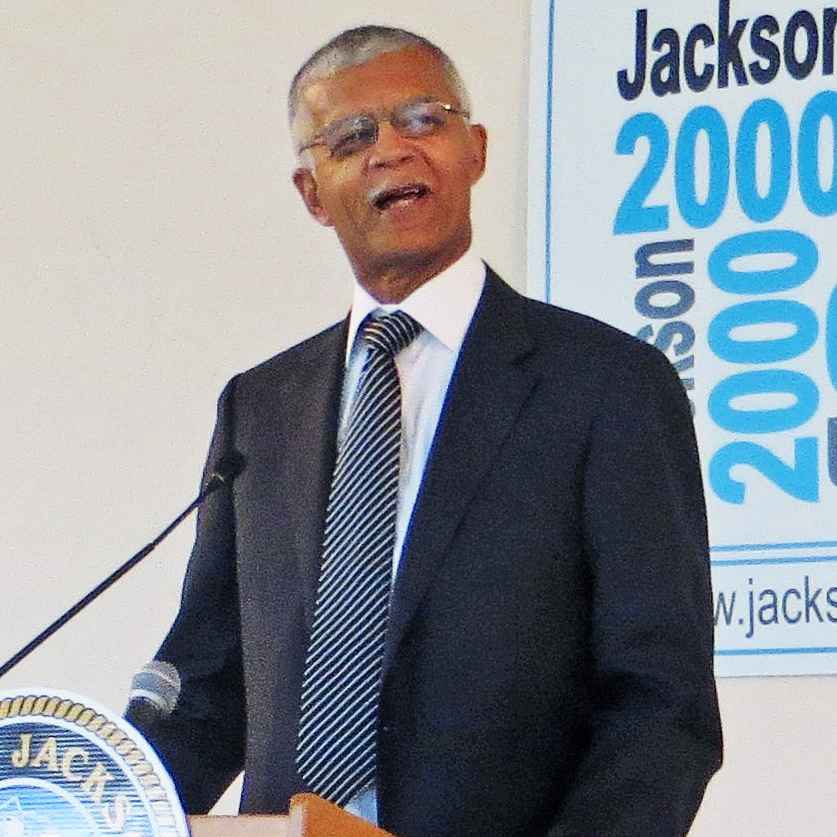

Chokwe Lumumba

Born in the public housing projects of Detroit’s West Side in the 1940s, he witnessed police brutality and racism from educators, neighbors and law enforcement. This propelled his activism at a young age, fighting against black discrimination and taking on white power structures through college.

At Wayne State Law School, he fought to change the school’s discriminatory grading system that initially resulted in 75% of black students in his class receiving failing grades. His victory resulted in honors for his classmates.

During his legal career, Lumumba drew on his experiences to take on racist institutions. As a staff attorney with the Detroit Public Defender’s Office, Lumumba provided free counsel to indigent clients during their criminal cases. They included Geronimo Pratt, a Black Panther who spent 27 years wrongfully imprisoned, as well as Assata Shakur and the late Tupac Shakur.

One of Lumumba’s most memorable cases was the defense one of the “Pontiac Sixteen,” who faced murder charges and a possible death sentence following a prison protest against unsanitary prison conditions and guard brutality.

In the late 80s, Lumumba moved to Jackson, Mississippi. He was integral in combating racism in Jackson’s public schools and curbing gang violence. He was elected to the City Council in 2009 and as Mayor in 2013, which his where he served until his death in 2014.

“When it comes to the discussion of oppression in America, we've been experiencing the worst of it for a long time. What's exciting to me is the prospect of going from worst to first in a forward-moving transformation which is going to take groups of dispossessed black folks here and others and make us controllers of our own destiny.”

In the face of daunting odds, Chokwe Lumumba's resilience and empathy provides a template for criminal justice advocates today.

Cora Mae Brown

At eight-years-old, Cora Mae Brown moved from Alabama to Detroit and grew to lead political movements for equity and criminal justice reform. In 1952, Brown became the first woman, and first black woman, to be elected to a state Senate, serving in Michigan.

A lifelong social justice advocate, Brown experienced racial discrimination as an elementary school student in Detroit. In 1931, she graduated from Cass Tech High School and then attended Fisk University in Nashville. There as a college student, when a young black man accused of rape in Tennessee was lynched in 1933, Brown became very involved in a demonstration and political movements on campus. Later in 1956, the Detroit Free Press noted that Brown’s involvement in that demonstration launched her life’s work against injustice and inhumanity.

After graduating from Fisk University with a degree in social work, Brown returned to Detroit as a social worker, including with the Women’s Division of the Police Department. Later she became a policewoman for the Detroit Police Department from 1941 to 1946.

Preparing legal cases at work inspired Brown to study law. And in 1948, Brown earned a law degree from Wayne State University, then explored running for public office. Four years later, Brown became the first black woman elected to the Michigan Senate. Throughout her two terms, Brown was a pioneer in civil rights. She supported legislation for fair housing and equal employment.

When she ran for Congress and lost in 1956, Brown was appointed Special Associate General Counsel of the U.S. Post Office one year later. Thereafter, she served as executive director of the President’s Committee on Government Contracts, which was formed to ensure that private firms contracting with the government complied with fair employment practices.

A social worker, lawyer and politician, Cora Mae Brown was diligent, battling injustice in each community she served.

In response to her election in 1952, Brown told the Detroit News: “These women voters have awakened and they expect their views to be properly represented. Women have always been able to bring sound and humane reasoning into everyday life. I believe they are the hope of the country.”

Erma Henderson

Erma Henderson was the first black woman elected to serve on the Detroit City Council. Henderson’s lifelong commitment to stand up for justice, in her own words, is “also a call to young people – all young people – to reach higher than you ever imagined yourself to achieve.”

Throughout her life, Henderson was dedicated to achieving racial equality. In the 1950s, Henderson worked to ensure black people were allowed into hotels and restaurants.

At the beginning of her career in politics, Henderson led Detroit Common Council campaigns for Rev. Charles Hill in 1945, then for William Patrick in 1957—Patrick was elected and became the first black City Councilman since the 1800s. Then, a year after the 1967 civil disturbance, Henderson became Executive Director of the Equal Justice Council, and collected data to evaluate how the judicial system treated black people.

In 1972, Henderson won her own seat on the Detroit City Council and became the first black City Councilwoman. In her role, Henderson lobbied for equal rights, targeting discriminatory loan and insurance practices called redlining, in which minority recipients were given less favorable rates, terms and conditions. Three years later, she organized the Michigan Statewide Coalition Against Redlining, which led to comprehensive state legislation that outlawed the practice.

In 1977, fellow members elected Henderson President of the Detroit City Council. She served 12 years in that role. In 1978, the Detroit News named Henderson a notable “Michiganian of the Year.”

“When I ran for Detroit City Council in 1972, opponents tried to tell me who I was and why I would not win. They said that I was poor, that I was African American, and that I was a woman. I replied to them that, ‘I may be poor, and I am African American, and I am a woman, and I am going to win this election.’ So think carefully about who you say you are.” – Erma Henderson

Richard Griffin

Richard Griffin

Richard Griffin leads through his actions, but through his words as the ACLU of Michigan’s Smart Justice Field Organizer in Grand Rapids. In his role, Richard is dedicated to ending mass incarceration in this country, starting with Michigan, first by recognizing that this carceral state is an extension of slavery.

Smart Justice is an ACLU of Michigan campaign that is working to cut the state prison population in half and end racial disparities in our criminal justice system. It’s campaign goals that require the grit and dedication of a person like Richard’s to achieve. And it’s a transformation in the system that Richard believes in and demonstrated himself, as he changed his entire outlook on life. A man who served time in Michigan’s corrections system, Richard was hired to take on this campaign because he is a leader.

Richard made a conscientious effort to make opportunity when there were none as an inmate of 23 years in Michigan, and decided to dedicate his life to improving the lives of others. When he was released, Richard came full circle: he reentered the Kent County community he grew up in with intent. Richard spoke his passion to transform the criminal justice system into reality.

Building coalitions and an army of campaign volunteers to follow his passion to reform the criminal justice system, Richard is an inspiration to those around him. To see Richard in action, from training volunteers to engaging the public, is to witness the power that will correct our corrupted system.

Richard’s favorite quote may best describe his life: "No tree, it is said, can grow to heaven unless its roots reach down to hell." Or in Richard’s own words: "To grow spiritually and emotionally, we will go to some rough places along the way because our greatest success is tied to our worst experience."