Ending Juvenile Life Without Parole: The Long Struggle for Second Chances

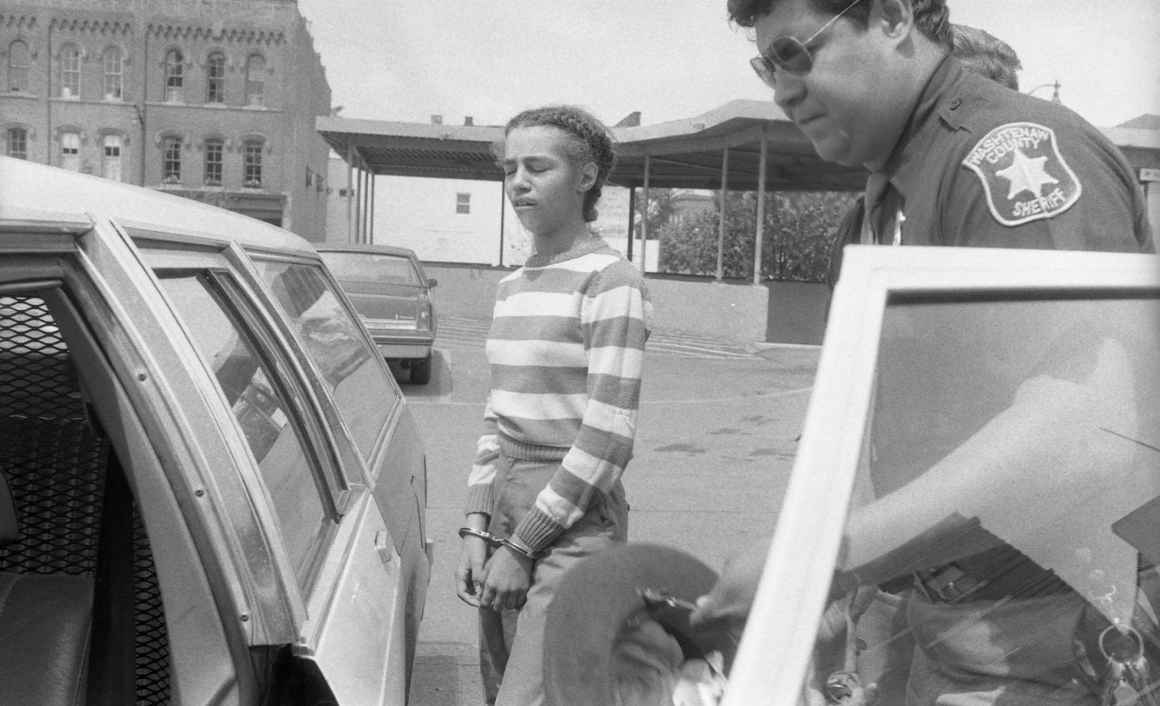

Sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole at the age of 17, Machelle Pearson held fast to one hope for more than 34 years.

“Despite everything, I always believed that I’d get out someday,” she says.

Now 52, Ms. Pearson has endured unspeakable trauma. She was 12 years old when her mother died. After that, her stepfather began molesting her. To escape, she ran away from home, eventually hooking up with a man who turned out to be an abusive drug addict. When she was 17, the boyfriend coerced her into committing an armed robbery that went awry, ending in the victim’s death. Though she’s always claimed the gun went off by accident, Ms. Pearson was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

While a prisoner, she was raped by a guard and became pregnant, giving birth to a boy. Ms. Pearson last saw her son, who was adopted, when he was just five. That was 22 years ago. Remarkably stoic when talking about the horrors she has faced, tears roll down her cheeks when the subject turns to the child she’s had no contact with for two decades.

“He’s my one soft spot,” she confesses.

Dave Walton has a similar story.

At the age of 13, he was brutally raped. He never reported the crime or told his family. His buried secret festered for years, eating away at him. He began running with what he calls a “bad crowd,” drinking and doing drugs. At 17, he got in an argument with another teen, engaging in a struggle over a gun that ended in death. He too was locked away in an adult prison, where he was gang raped.

“In a way, that was even harder to deal with than what happened to me when I was 13, because I was older, and felt like I should have been able to protect myself,” he says, still shaken by the hurt and shame decades after the assault.

Along with surviving sexual abuse in and outside of prison, and receiving life without parole sentences for murders they say were unintentional, Mr. Walton and Ms. Pearson have something else in common: Both gained their freedom as the result of a relentless legal battle, mounted by the ACLU of Michigan and others, to get the courts to recognize that sentencing juvenile criminals to life in prison without the possibility of parole constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

Juvenile Justice A Longstanding Priority

The ACLU of Michigan’s fight to end juvenile life without parole sentences is a clear example of the persistence often necessary to obtain justice. The United States is the only country in the world that allows children to be punished with life in prison without the possibility of parole, and Michigan has imposed this sentence on more children than all but one other state.

The ACLU of Michigan made the issue a priority in 2005, publishing a report entitled Second Chances, which called for an end to this inhumane practice. As explained in the report: “Altogether, the body of research on adolescence supports the conclusion that juveniles are not as culpable for offenses as adults, because they lack the same maturity necessary to control their actions and understand the consequences of those actions.” This growing body of research led the U.S. Supreme Court to finally eliminate the death penalty for juveniles in 2005, but Michigan and some other states continued locking children away with no chance of release.

In 2011, the ACLU of Michigan filed Hill v. Granholm, a federal class action lawsuit challenging juvenile life without parole in Michigan. While that was pending, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that laws requiring the mandatory imposition of life-without-parole punishments on juveniles are unconstitutional, again recognizing the growing research and scientific consensus that teenagers are both less culpable than adults and more capable of rehabilitation. Warning that “imposition of a State’s most severe penalties on juvenile offenders cannot proceed as though they were not children,” the court ruled that automatically locking kids up for life without a meaningful opportunity for release violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual” punishment.

Following the Miller decision, a federal judge in Detroit ruled in favor of the ACLU in the Hill case and ordered Michigan to develop a plan for giving all its 363 juvenile lifers meaningful parole consideration. But then-Attorney General Bill Schuette refused to comply with that order and argued on appeal that that juveniles already sentenced to life without parole were not entitled to resentencing, and should never even have their cases reviewed by a parole board. The wrong-headedness of Schuette’s cruel contention was fully exposed in 2016 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Miller must be applied retroactively, finally vindicating the ACLU’s position that children must be given at least the opportunity of second chance.

But the fight to obtain justice for these juveniles was not over, because the Michigan Legislature had passed a new law in 2014 intended to undermine the Hill decision by authorizing state judges to keep people sentenced as children locked up as long as possible, no matter how unfair the circumstances might be. The law even mandated that these prisoners could not be granted credit for good behavior—credits that would otherwise allow significant amounts of time to be shaved from their sentences.

Fortunately, the federal Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals did not allow the new law to go unchecked. The court ruled in August 2018 that the elimination of good-time credits was unconstitutional, and sternly rebuked the state, saying, “It is well past time to put to rest litigation tactics and further delay.”

Our Work Remains Unfinished

One of those people is Kevin Boyd.

In August 1994, Mr. Boyd – who was physically abused by his alcoholic parents -- was 16 when he was convicted of conspiring with his mother to kill his father. Following his parents’ divorce four years earlier, he’d attempted suicide and bounced from school to school until dropping out completely when just a sophomore. Offering the prospect of a big insurance payoff, Mr. Boyd’s mother recruited him to help kill her estranged husband. No evidence put him at the scene of the crime, and his mother (who also received a life without parole sentence) testified that Mr. Boyd wasn’t present when the murder was committed.

In the more than two decades since then, Mr. Boyd has earned a high school equivalency diploma, tutors other prisoners, and has gone 15 years without a misconduct violation. "I've demonstrated no violent behavior," he told a reporter from the Free Press in 2017. "I've had no substance abuse issues. ... I am not even a reflection of who I used to be."

Despite that, prosecutors continue to contend that he should die behind bars. A judge was scheduled do decide his fate in April.

Instilling Hope

An attorney in private practice who heads up the ACLU of Michigan’s Juvenile Life Without Parole Initiative, Deborah LaBelle has been at the forefront of the fight to give kids a second chance.

In 2014, Ms. LaBelle received a hand-written letter from Lamonte Card, a 42-year old man who’d been locked up for murder since the age of 17. The letter, which LaBelle would sometimes read from when talking with various groups, was not seeking help, even though Mr. Card had been behind bars for more than two decades at that point. Instead, he wanted only to thank the ACLU for its efforts, on behalf of all of Michigan’s juvenile lifers, and to express how this work created the hope necessary to continue working toward returning to their communities.

“Thank you for demonstrating what it is to focus on what we CAN do rather than worrying about what we CAN’T do. You are an inspiration to me,” he wrote.

Asked recently why he wrote that letter, Mr. Card responded: “My whole life I grew up thinking no one cared, but here were these people fighting so hard for me, showing how much they cared. It was like throwing me a lifeline.”

In 2018, having spent most of his life in prison, Mr. Card was able to win his release.

Adjusting To New Lives

Learning to drive, getting a job, adjusting to technology, cell phones, navigating the adult relationships, after decades behind bars -- all of this and more are steep hills these returning citizens must climb.

One thing both Mr. Walton and Ms. Pearson have done to help cope with these same challenges is to spend much of their time helping others, especially young people.

“I guarantee, if you can get to them, you can change their whole program,” says Mr. Walton. “That’s my mission now.”

Both Mr. Walton and Ms. Pearson also know they are fortunate to have been released while more than 200 other juvenile lifers remain locked up. So they are willing to reopen deep emotional wounds, talking about their experiences, with the hope it will help spread the message that the people locked up as kids are not monsters as they often have been portrayed. And that the fight to obtain justice for them will not end until all have had a real chance at going free.

“We made tragic mistakes,” says Ms. Pearson. “But people need to keep in mind that we were only kids, and that we can all change.”